Introduction: Boost Agility Through Better Decision-Making

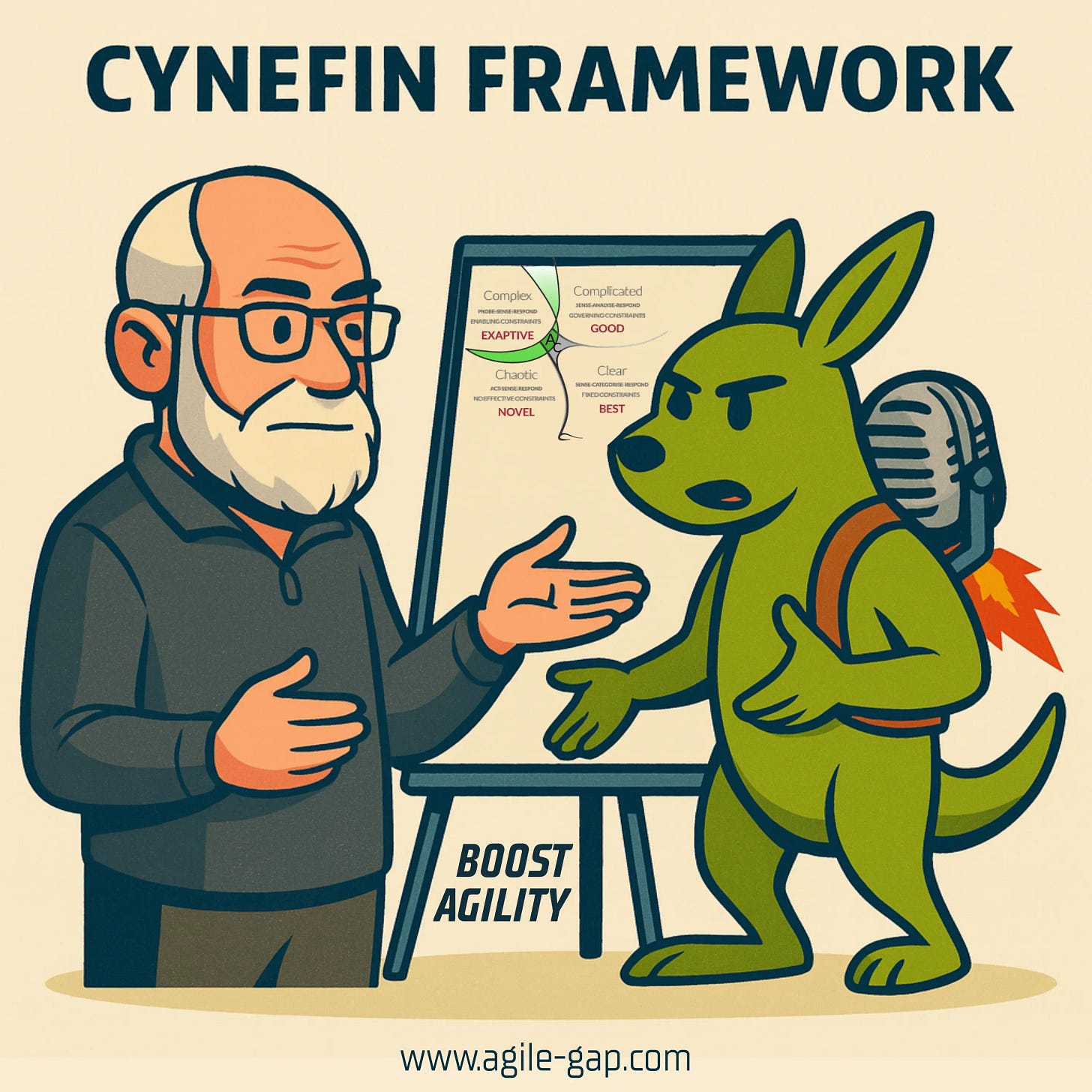

Welcome to today’s episode. In this session, we’ll explore how leaders and teams can boost agility by applying the Cynefin Framework. This decision-making tool, created by Dave Snowden in 1999 at IBM Global Services, helps people understand the nature of situations before taking action. Snowden described it as a sense-making tool, a way to interpret reality so that organizations can respond effectively and flexibly. The Welsh word Cynefin means “habitat,” reminding us that context shapes every choice we make.

While many know the Cynefin Framework from simplified diagrams—such as those popularized by Edwin Stoop—the true value lies not in the drawings but in how it boosts agility by guiding decisions in different contexts.

The Origins of Cynefin

Snowden designed the model to help IBM manage knowledge more effectively. As European director of IBM’s Institute of Knowledge Management, and later as founder of the IBM Cynefin Centre for Organizational Complexity, he refined the framework into a globally recognized tool. In 2003, Snowden and Cynthia Kurtz published The New Dynamics of Strategy: Sense-Making in a Complex and Complicated World in the IBM Systems Journal, a paper that established Cynefin as an innovative framework.

Over time, the domains evolved: from “known, knowable, complex, and chaotic” in 2003, to “simple and complicated” in 2007, and later to “clear.” This evolution reflects the same principle that organizations must adapt continuously if they want to boost agility in uncertain environments.

The Five Domains That Boost Agility

The Cynefin Framework divides decision-making into five domains: clear, complicated, complex, chaotic, and confusion. Each domain provides a different way to interpret cause and effect, offering leaders guidance on how to act.

1. Clear Domain

The clear domain is the world of known knowns. Rules and best practices apply, and outcomes are predictable. The method is sense–categorize–respond. By identifying facts, categorizing cases, and applying proven methods, organizations can ensure stability. However, clinging too tightly to “clear” processes can block innovation. Leaders who want to boost agility must prevent complacency by encouraging early warnings and fresh perspectives.

2. Complicated Domain

Here, cause and effect exist but require analysis or expert knowledge. This is the domain of engineers, analysts, or medical specialists. The approach is sense–analyze–respond. Multiple correct solutions may exist, and the best path depends on expertise. Organizations that learn how to navigate complicated systems effectively can boost agility by balancing expert insight with adaptive learning.

3. Complex Domain

Complex situations involve unknown unknowns. Patterns only appear after experiments and reflection. The move is probe–sense–respond. Leaders can boost agility by running safe-to-fail experiments, learning from feedback, and scaling successful approaches. This domain is essential for navigating culture, markets, and ecosystems where rigid rules fail but adaptive learning thrives.

4. Chaotic Domain

The chaotic domain is the world of crisis, where immediate action is required. The approach is act–sense–respond. First create stability, then evaluate, and finally respond. Acting decisively in chaos allows organizations to boost agility under extreme pressure. Examples include disaster recovery, emergency response, or major organizational breakdowns.

5. Confusion Domain

At the center lies confusion, where it is unclear which domain applies. Conflict, noise, and disagreement dominate. To move forward, break the issue into smaller parts and place each into one of the other domains. By clarifying complexity, organizations can boost agility and regain momentum.

Movement Between Domains

The Cynefin Framework is dynamic. Problems may move clockwise from chaotic to complex, to complicated, and finally clear. But bias or complacency can cause a sudden collapse from clear into chaos. By recognizing these shifts, organizations can continuously boost agility and adapt to new realities.

Real-World Applications of Boosting Agility with Cynefin

The Cynefin Framework has been used across industries to boost agility:

At IBM, teams applied it to policy, product development, supply chains, and customer service.

Governments applied it in emergency response, defense, and policy-making.

Healthcare professionals used it in the NHS and in the fight against HIV/AIDS in South Africa.

Agile teams employed it to handle uncertainty in software development.

Security and crisis teams applied it to homeland security, policing, and large-scale disruptions.

In 2017, RAND reviewed decision models with Cynefin, while the European Commission published field guides for applying it in crisis management.

Criticism and Limitations

Some critics argue the Cynefin Framework is too abstract or lacks clarity in its terminology. Others say it oversimplifies the real complexity of organizational life. Yet many researchers argue the opposite: that Cynefin helps organizations face uncertainty directly, thereby enabling them to boost agility when theory alone is not enough.

Cynefin and the Theory of Constraints

Steve Holt compared Cynefin with the Theory of Constraints, mapping different types of constraints to Cynefin’s domains. This cross-application highlights how both frameworks can be used together to boost agility by aligning decision-making with systemic bottlenecks and adaptive constraints.

Conclusion: Boost Agility by Understanding Context

Not all problems are the same. Some require best practices (clear), others expertise (complicated), others experimentation (complex), and crises demand immediate action (chaotic). Sometimes confusion itself is the first challenge.

By applying the Cynefin Framework, leaders and teams can recognize the context of their challenges and act accordingly. This ability to adapt decision-making styles is what allows organizations to boost agility, thrive in uncertainty, and create sustainable success.